Review

“Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit (1926)” vs. “Die entfesselte Menschheit (1920)”

Translated from: P. Stiasny, “Das Kino und der Krieg, Deutschland 1914–1929”, München 2009, pp. 228-230.

Lukewarm Second Serving

Years after Die entfesselte Menschheit ran in cinemas, large parts of it reappear in 1926 in Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit. Now the story has been recut and the protagonists have been given new names: again, the film begins with war captivity, the return to Germany and the conflict between reformers and revolutionaries.

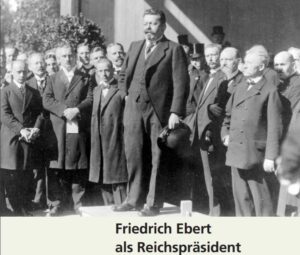

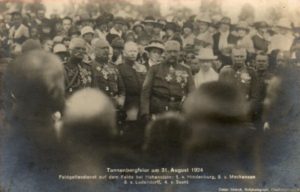

After the uprising fails,  the plot jumps back to 1925, which is illustrated by interwoven documentary footage of Friedrich Ebert’s funeral and Hindenburg’s election as new Reich President. The communist party leader Dorn (formerly Karenow) reassembles a group of conspirators around him who aim to overthrow the republic via acts of kidnapping, theft, extortion and incitement to strike. In the end, Dorn dies trying to save Louise (formerly Rita), the wife of his rival Frank (formerly Clarenbach), from the mob. Dying, he sends a message to his deputy Brüggemann (formerly Winterstein): “Tell Brüggemann the slogan for the presidential election must be: Only through work, can there be construction!”

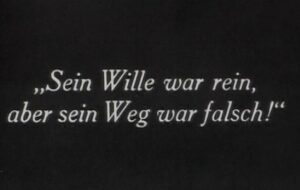

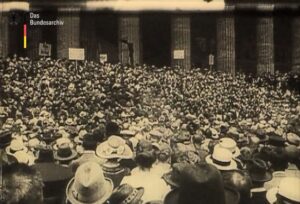

the plot jumps back to 1925, which is illustrated by interwoven documentary footage of Friedrich Ebert’s funeral and Hindenburg’s election as new Reich President. The communist party leader Dorn (formerly Karenow) reassembles a group of conspirators around him who aim to overthrow the republic via acts of kidnapping, theft, extortion and incitement to strike. In the end, Dorn dies trying to save Louise (formerly Rita), the wife of his rival Frank (formerly Clarenbach), from the mob. Dying, he sends a message to his deputy Brüggemann (formerly Winterstein): “Tell Brüggemann the slogan for the presidential election must be: Only through work, can there be construction!”  Frank endorses this message and reconciles with his wife, kneeling at the body of Dorn. He admits: “His will was pure, but his way was wrong!” A leap: Hindenburg is elected as the new Reich President. Documentary footage shows gatherings of people in Berlin, Hindenburg’s journey through the Brandenburg Gate and his arrival in the Reich President’s Palace.

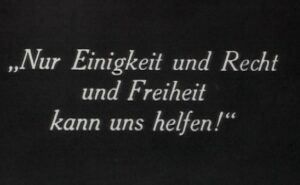

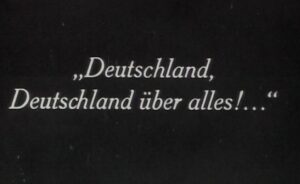

Frank endorses this message and reconciles with his wife, kneeling at the body of Dorn. He admits: “His will was pure, but his way was wrong!” A leap: Hindenburg is elected as the new Reich President. Documentary footage shows gatherings of people in Berlin, Hindenburg’s journey through the Brandenburg Gate and his arrival in the Reich President’s Palace.  Brüggemann, who was wounded during the unsuccessful uprising, has recovered from his injury. He hosts old party comrades at his apartment and tells them that they can no longer count on him because he has completely revised his political views. He proclaims: “Only unity and law and freedom can help us!” The last title reads: “Germany, Germany above all!” Alongside Elge (Elga Brink), a newly inserted figure, Brüggemann searches private happiness.

Brüggemann, who was wounded during the unsuccessful uprising, has recovered from his injury. He hosts old party comrades at his apartment and tells them that they can no longer count on him because he has completely revised his political views. He proclaims: “Only unity and law and freedom can help us!” The last title reads: “Germany, Germany above all!” Alongside Elge (Elga Brink), a newly inserted figure, Brüggemann searches private happiness.

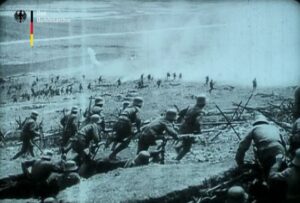

In comparison with Die entfesselte Menschheit, documentary footage and reshot fictional scenes were added. Elsewhere, scenes and figures were deleted: Winterstein’s escape from the prisoners of war camp, his involvement in Karenov’s troops in Russia; completely missing are the conspirators Menschenholz and Breese as well as Rosa Valetti, a lustful “shotgun dame”. The earlier film restored order by killing two leaders of the insurgents, Karenow and Winterstein, whereas the latter film grants at least one of the two, the German, a happy ending. However, the prerequisite for this is that Winterstein defects to the consensus ideology in the newly shot ending, which in turn makes the film look like a commercially motivated, opportune statement on the status of history and memory politics.

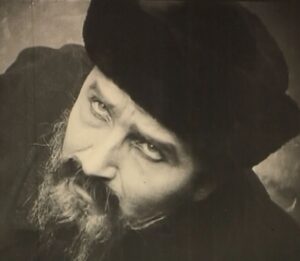

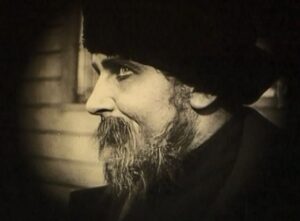

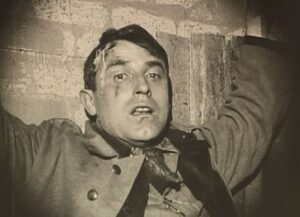

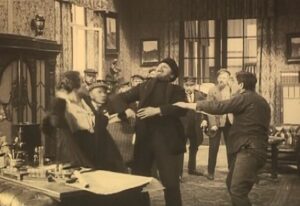

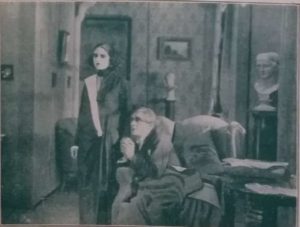

The end of the revolutionary leader, who perishes during the rescue of a woman and is then recognized by his ideological opponent as a man with a “pure will”, is the same in both films. This glorification is particularly strange because before the end there is actually no reference to the human qualities of Karenow or Dorn: on the contrary, the  revolutionary leader appears as a coldly calculating and dogmatic exponent of destruction and violence endowed with great criminal energy and uncanny charisma towards women. For a moment, a melodramatic relationship flares up between him and his rival’s wife: she is enthusiastic about his ideas and helps him flee while he dies in return to save her. But that does not hide the fact that there is a contradiction between the visual representation and the texts of the subtitles. Judging from the surviving material, it is a bold assertion that Karenow is a revolutionary who is “blinded by holy idealism and inspired by the noblest love of people”, as the magazine Film Kurier asserts. This claim is explained through what he says in the subtitles, but not by how he says it and how his appearance, gazes and gestures are staged.

revolutionary leader appears as a coldly calculating and dogmatic exponent of destruction and violence endowed with great criminal energy and uncanny charisma towards women. For a moment, a melodramatic relationship flares up between him and his rival’s wife: she is enthusiastic about his ideas and helps him flee while he dies in return to save her. But that does not hide the fact that there is a contradiction between the visual representation and the texts of the subtitles. Judging from the surviving material, it is a bold assertion that Karenow is a revolutionary who is “blinded by holy idealism and inspired by the noblest love of people”, as the magazine Film Kurier asserts. This claim is explained through what he says in the subtitles, but not by how he says it and how his appearance, gazes and gestures are staged.

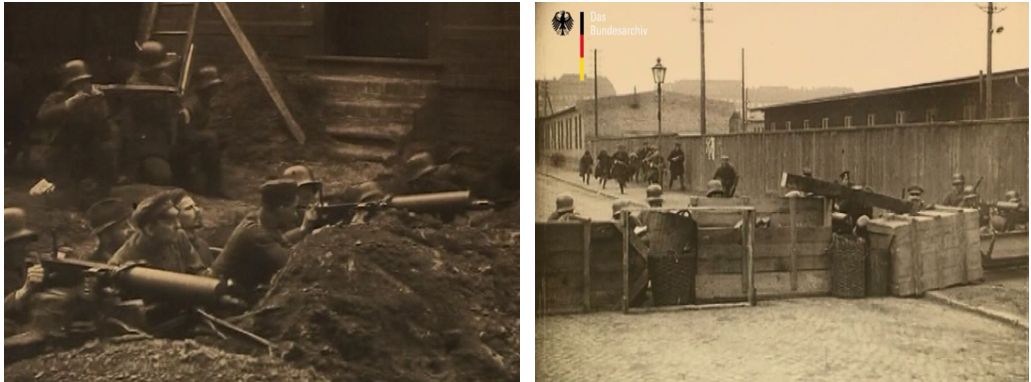

Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit passed the censorship without difficulties in May 1926 but found little resonance afterward in the specialist and daily press. After the premiere in Munich in October 1926 in the somewhat remote neighborhood of Obergiesing, the Süddeutsche Filmzeitung sums up the film, which deals with “the conversion of two revolutionary […] people into constructive, bourgeois elements of society” and staged the Berlin street fights well. “Since the revolution, social films did not disappear from German production, even if it […] did not have strong productions […]. It just seems to be the fate of biased films, no matter what political direction they take, that their strength is in inverse relation to their consciousness.” The cinema audience of 1926 has surely perceived Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit as a greeting card from a distant past. Film aesthetics and viewer expectations changed too quickly between 1920 and 1926, for a reasonably demanding audience not to notice the outdated mise-en-scène. And the political climate changed too quickly for a film about revolution and civil war, not to be viewed as a foreign body in entertainment cinema.

It is uncertain whether the re-editing of Die entfesselte Menschheit paid off commercially for the production company Nivelli-Film, but it can be doubted. On the one hand, Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit reminds us of the quite common practice to re-make a film that has already been successful here and there to increase its chances for additional markets. On the other hand, it is quite strange how the plot is twisted here and the film is very obviously adapted to the politics of the day through new scenes and added documentary footage. The somewhat dusty Die entfesselte Menschheit is virtually correctly “renovated” in terms of history and politics and put into circulation again under a new, strikingly chosen name: a fraudulent labeling. This reminds us a little of the transformation of the Adler von Flandern into Ikarus in 1918/19. Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit, as well, is a defector.

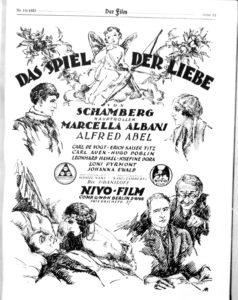

Cast

Paul Hartmann – Kurt Frank, technical director of Stoltenberg Works

Trude Hoffmann – Luise, Frank’s wife

Clementine Plehsner – Mrs. Möhricke, landlady

Elga Brink – Elge, her daughter

Eugen Klöpfer – August Dorn, tenant of Mrs. Möhricke

Carl de Vogt – Walter Brüggemann, tenant of Mrs. Möhricke

Hermann (Heinrich) Backmann – Richard Stoltenberg, owner of Stoltenberg Works

Arthur Bergen – Egon, his son

Marion Illing – Clara

Photo Gallery

(click on any photo to start a slide show)

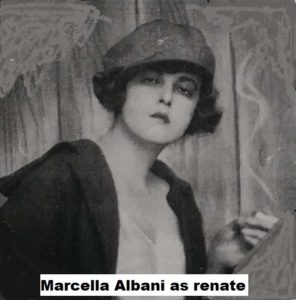

Marcella is too ashamed to admit to her new situation. She asks for his forgiveness and tells him that he will be able to understand her actions later on.

Marcella is too ashamed to admit to her new situation. She asks for his forgiveness and tells him that he will be able to understand her actions later on.

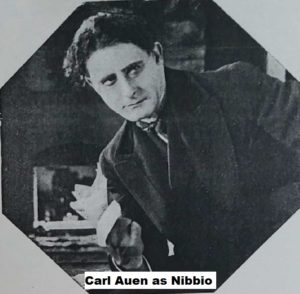

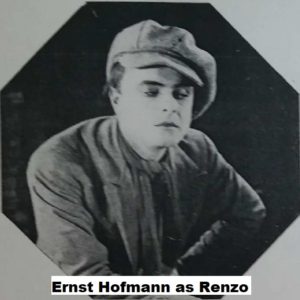

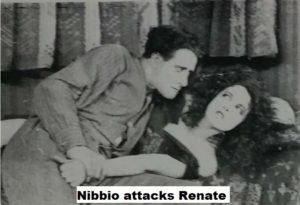

At first, he tries to seduce her with words but when he realizes that she is lost to him, he threatens to tell the doctor that she used to be his lover. When he becomes violent, Renate is left with no other choice but to shoot him with a revolver.

At first, he tries to seduce her with words but when he realizes that she is lost to him, he threatens to tell the doctor that she used to be his lover. When he becomes violent, Renate is left with no other choice but to shoot him with a revolver.