The Rise of Film Censorship – Nivelli vs. the Censor

As cinema was becoming more and more popular, the government was concerned about its potential to corrupt impressionable elements in society, such as the youth. Before WWI, there was no specific regulation applicable to film, but many films were still cut or completely banned. Following the end of the monarchy in 1918, theatre and press censorship were cancelled with the exception of films and by 1920, a uniform film censorship bill was introduced through the “Reich Motion Picture Act” (Reichslichtspielgesetz). The bill was enforced by the “Film Review Office” (Filmprüfstelle) with the purpose of checking for pornography and other indecent content and also assessing security considerations, such as perceived cases of danger to interests of the state, or threats to public order.

Each film had to be submitted (usually by the production company) for examination by a review board, either in Berlin or in Munich, prior to its release to the cinemas. Appeals against rulings were decided in Berlin by a “Supreme Review Office” (Film-Oberprüfstelle).

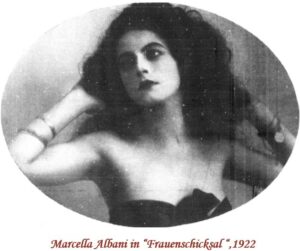

Many of Nivelli’s films were romantic melodramas and naturally included “romantic moments”, which at the time might have been considered suggestive. Consequently, they all received the “banned for minors” label from the censor. Several of his films encountered additional rejections. For example, Nivo-Film was required to cut-out several  scenes from the film “Women’s fate” (Frauenschicksal 1922), which were deemed “crude”, such as: when “policemen are handling a woman roughly when she offers resistance”, or when “an elegantly dressed gentleman is assaulted and then robbed by some young hooligans”. In another instance, the ruling on the film “In the Heat of Passion” (Im Rausche der Leidenschaft 1923), caused Nivo-Film to file an appeal. This time the initial decision was overturned and previously rejected scenes were allowed to remain, such as a partially-naked torso of a woman. The committee was of the opinion that there was no intent to create “an erotic impact” and therefore it “did not qualify to influence the fantasy of healthy adolescent people in an adverse manner”. Naturally, the considerations of the censor are a good indication as to the moral standards and social codes of conduct that were acceptable at the time.

scenes from the film “Women’s fate” (Frauenschicksal 1922), which were deemed “crude”, such as: when “policemen are handling a woman roughly when she offers resistance”, or when “an elegantly dressed gentleman is assaulted and then robbed by some young hooligans”. In another instance, the ruling on the film “In the Heat of Passion” (Im Rausche der Leidenschaft 1923), caused Nivo-Film to file an appeal. This time the initial decision was overturned and previously rejected scenes were allowed to remain, such as a partially-naked torso of a woman. The committee was of the opinion that there was no intent to create “an erotic impact” and therefore it “did not qualify to influence the fantasy of healthy adolescent people in an adverse manner”. Naturally, the considerations of the censor are a good indication as to the moral standards and social codes of conduct that were acceptable at the time.

Other Nivelli films came under the category of potential “danger to interests of the state, or threats to public order and security”. The political melodrama “Humanity Unleashed” (Die entfesselte Menschheit 1920) was drawing a lot of attention from the press even while it was still being filmed. This sparked concern by the government regarding the effect which the film might have on Germany’s image abroad. The Foreign Office got involved and Max Nivelli was summoned. Only after their representative viewed the film, it was finally approved by the censor.

But even a supposedly harmless short film got Nivelli into a clash with the censor. This was a short documentary about the 10th-anniversary ceremony of WWI in honor of the fallen soldiers. The ceremony was attended, among others, by three of the former Crown Princes, the sons of Emperor Wilhelm II. The Weimar government was extremely sensitive to Germany’s new image as a democracy. Any emphasis on royalty in conjunction with the military, was suspected to give rise to new incitement against Germany abroad, or disrupt public order at home. It took several deliberations of the censor, an appeal by Nivo-Film and finally the summons of expert delegates from the Foreign Office, the Prussian Home Office and the Commissioner for Public Order and Safety, before the documentary was approved. Nevertheless, the scenes where the Crown Princes were seen next to men in uniform, had to be cut-out. Nivo-Film still had to pay the costs of the proceedings because not all objections were lifted.